Biopharma without borders - commercial model for niche specialty care and orphan products

Specialty care and orphan products are on the rise, with the latter alone now expected to reach a sales value of $178 billion by 2020. But with the traditional affiliate-based model too resource-dependent for getting specialty care and orphan drugs to global markets, companies are realizing the need for a supranational cross-border approach to generate critical mass and focus for their innovative offerings. Here we outline various cross-border approaches, provide tips on how to identify the most suitable one for your product and outline the crucial steps to build a supranational business unit.

From blockbusters to niche busters

The healthcare environment has changed almost beyond recognition in the past decade and this has been well documented. One of the key upshots of the turbulence caused by healthcare reforms, patent cliffs, drying product pipelines, fiscal restraint and a host of other factors, is that many pharmaceutical companies have shifted their attention to specialist care and rare disease products.

In many ways it has been a natural evolution. Advances in genomics and biotechnology have revolutionized drug development leading to many specialized, targeted treatments, mainly in oncology and immunology. The number of orphan drugs coming to market is increasing, and this represents a particularly attractive segment, with an estimated compound annual growth rate for 2015 to 2020 of +11.7%, reaching a projected global sales value of $178 billion. The growth rate is almost double that of the overall prescription market. Orphan drugs are set to be 20.2% of worldwide prescription sales by 2020.

So it’s easy to see why companies want to invest in this area. But what is the best way to bringing such products to market?

New models needed for niche specialty care and orphan drugs

Given the often very small patient numbers and specialist treatment centers associated with niche specialty care and orphan drugs, more tailored and nimble commercial models are required to get them into the hands of the patients who need them.

A potential solution is the creation of a ‘supranational’ business unit, which sits above country borders, potentially at a regional level or at a ‘cluster level’ (serving a certain number of Centers of Excellence). This business unit can connect rare disease Centers of Excellence, KOLs and patients across different countries, managing them all from a single, central resource. It also provides organizations with visibility over people and processes involved in one disease area, with central monitoring of customer facing roles.

Several such models have been successfully developed and implemented in recent years, and many of our own clients have implemented new organizational structures separate from their other organizations typically set-up in affiliate structures (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Supranational commercial models our consultants supported

So the good news is that many successful organizational models have been implemented already. Some are set in stone and are here to stay; others have been set-up temporarily, often in transitionary periods such as for a successful launch.

But when should you apply such a model? And exactly which one suits your exciting niche specialty care / orphan drug?

Going supranational: a nimble, tailored approach

There has already been a move to globalize key processes, systems and models in recent years. For example, commercial and regulatory pressures - including regulatory demands both for simultaneously more information and greater consistency - are causing pharmaceutical companies to have to manage regulatory information at a global level across the enterprise.

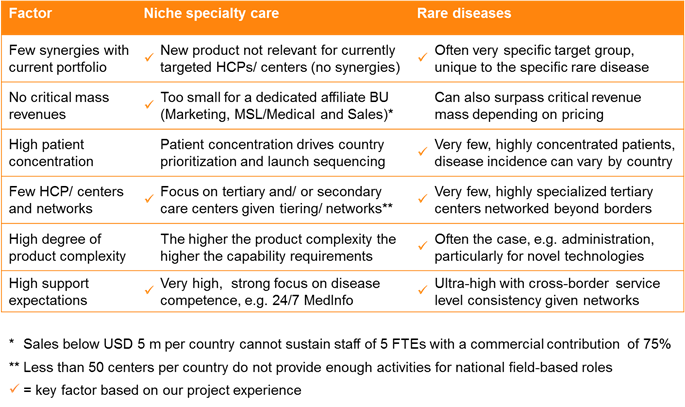

When it comes to niche specialty care and orphan drugs, there are several factors (listed in the left hand column of Table 1, below) which can be assessed to understand if a cross-border approach may be preferable to the traditional affiliate-based approach. The more of these factors your product aligns to, the more likely a globalized approach is the right one.

The most important is probably the first one – if there are few synergies with your current portfolio, then another novel approach is a much easier ‘sell’ internally. Meanwhile a high degree of product complexity – for example related to administration driven by novel technologies, such as cell therapy – increases the capability requirements significantly.

In a nutshell, the fewer patients there are and the more concentrated these are in highly specialized treatment centers, the more a supranational model makes sense.

Immediate benefits

For many niche products the affiliate-based model is impractical and economically unfeasible, so the cost saving is immediately apparent. Niche specialty care / orphan products with revenues below USD 5 million per country cannot self-sustain the minimum requirement of five full time employees (one Marketing, one Medical Affairs/MSL, three Sales Reps), assuming a commercial contribution target of 75% that many of our clients strive for.

In these cases, our clients have looked to supranational models for both office-based roles (e.g. Marketing, Medical Affairs) as well as field-based roles (e.g. MSLs, Sales Reps).

From theory into practice

Based on our rich project experience in this area, we have selected three scenarios to share key lessons learnt. In the summary box below each scenario, we focus on the key implementation challenges and the ‘dynamic drivers’ – in other words the factors that key decision makers within the organization considered which way to go next.

Scenario 1: The temporary growth booster

A mid-sized biopharma company decided to create a permanent Business Unit for a new product in an ultra-rare disease area. This required outreach to additional, unidentified healthcare stakeholders.

The Business Unit included countries across different continents. Many affiliates welcomed the opportunity to offload the costs given the positive impact on the profitability of their core business.

After a period of very strong growth, the company reintegrated the product back into country affiliates, based on their request. The company had made only a temporary initial commitment, waiting until affiliates wanted to have the more successful product back with significantly higher sales compared to before.

Scenario 2: The multi-purpose capability

A top 15 biopharma company invested in pan-European commercial capabilities, enabling them to launch products which fall below a certain critical mass in revenue.

These capabilities have been utilized both for temporary and longer-term means. For example, one highly complex product for a rare disease clearly didn’t have the capacity or engagement of affiliates at launch; it was handled at a pan-European level and is expected to be handed-over to the countries later on once established.

Meanwhile another orphan drug was launched by the European Business Unit to limit affiliate overinvestment. If this product evolves as expected, it is likely to remain permanently in the European business unit throughout its lifecycle.

Scenario 3: The cluster launch unit

Another top 15 biopharma company was preparing for the launch of a niche specialty care product in a new therapeutic area.

They realized that many small countries in Central and Eastern Europe struggled to dedicate adequate resources to build a critical mass organization, particularly for office-based roles, e.g. Marketing, Medical Affairs.

With that in mind, a dedicated organization was established to provide this level of support, and to manage and secure launch success in each of the markets where appropriate. If successful, the product should be handed back over to affiliates once it has surpassed the necessary revenue thresholds. Importantly, the same multi-country approach could also be considered for other regions in Europe and beyond.

4 crucial steps to building a supranational business unit

So, how do you go about setting up a supranational business unit? Below are four key steps on the journey.

Step 1) Establish governance rules

First, the governance rules for the new business unit need to be devised. The decision where the P&L ownership for the new business unit lies is vital. To ensure both decision-making power and adequate country support, some pharma companies have implemented creative account approaches, such as double P&Ls at supranational / national levels or centralized costs at the dedicated business unit level (also for affiliates local costs).

Very early on in the process, a clear understanding of the disease, particularly incidence and prevalence and number of treatment centers and stakeholders per country, is needed to create buy-in for the novel cross-border structure. Mapping out the patient journey at this stage can be useful as well. This will give pointers to the task ahead and the type of leader required to build such a new commercial set up.

Step 2) Choose the Business Unit Head

The leader of the new business unit needs to hold P&L ownership and should have a reporting line into a senior executive within the organization to demonstrate the importance of this new business unit to colleagues, particularly within the affected affiliates.

The Head should be tasked to focus on building an organization which has the following qualities:

- i) An entrepreneurial culture

ii) The ability to share information quickly cross-functionally

iii) Nimble, rapid decision-making processes

iv) A thirst to deliver top information and service to customers and patients

v) Customer level operational analytics for the covered countries

Step 3) Define dedicated competencies and roles

To deliver such an organization, the required dedicated competences have to be defined and developed. It is also important to decide where the respective competences need to be located – whether on the ground close to the customer or in a central back office. Relevant roles / capabilities can be mapped against the degree of specificity for indications and geographic markets (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Roles by specificity for indications and geographic markets

Customer facing roles, such as sales reps and MSLs, are of course locally implemented; however, these can be reporting into a central organization. Given the typically small number of field-based roles, sales and MSL managers often end-up managing team members located in multiple countries.

Other non-indication specific support functions can be centralized to avoid duplication and create critical mass, for example:

- Operational business analytics, e.g. CRM, performance dashboards

- Logistics/ supply chain, e.g. request management, order to cash

- Support processes, e.g. congress/event management, publications management

Country specific non indication-specific support, such as HR and payroll, needs to be provided locally. If a small biotech doesn’t have such capabilities available, outsourcing may provide the optimal solution.

Step 4) Manage potential duplications

The larger a company is, the higher the risk for overlapping functions or duplication of functions exists and, hence, the leadership needs to decide when to share these between the business unit and the incumbent structure and when to deliberately choose separation. Clearly, this is an important task for the Head and the management team of the new business unit and decide with their peers in affiliates and HQs.

What does success look like? 4 key benefits

We have been through the above four steps many times with different clients. The needs are always slightly different, but the steps on the journey are more or less the same.

But what benefits have we seen at the end of the journey? The outcomes are of course case-specific, but there are several overarching benefits that we see time and time again:

1) Improved customer interaction and satisfaction

The great thing about having one, core cross-border organization is that it gives you control and visibility over your people and processes – central monitoring of the customer facing roles, particularly sales reps, key account managers, medical scientific liaisons and medical education teams.

It means that any customer request can be dealt with quickly, with excellent, accurate content.

Such a customer-centric approach can provide a formidable competitive advantage. One of our clients has measured customer satisfaction regularly through quarterly quantitative surveys. From the very beginning, their centralized approach was far superior to a major competitor with a traditional affiliate structure. The competitor was forced to react to the increased customer expectations and change their own model. They moved the needle over time but never really caught up within the next year which, during a launch, is a long time (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Customer satisfaction measurement over time

2) Speed of organizational evolution

Creating a supranational organization can be achieved in ‘record time’, unlike building an affiliate infrastructure from scratch. This is an important consideration for smaller companies who are often in a race against the clock for their lead compound. For larger biopharma companies, if they have no similar products in their existing portfolio, this makes the affiliate route unappealing as well.

One of our clients has established a global holding in Switzerland with tax structures in Germany (sales from many EU countries), France, Italy and Spain. Further affiliate offices and systems were not needed, which is clearly an advantage in terms of cost and speed of implementation.

3) Cross-border best practice sharing

The multi-country set-up combined with excellent business analytics means a regional/ global organization can react quickly to local market dynamics.

For example, a large European treatment center needed support in the development of their local protocol. Our client’s organization very quickly linked them with a treatment center in another country which had developed their own protocol for a similar condition. This cross-country best practice sharing is increasingly expected in rare diseases where centers are already cooperating together in regional networks.

4) Optimized effectiveness, efficiency and profitability

This is a very efficient way of doing business. With a small field force, requiring no local infrastructure, with all duplicating activities eliminated, it is not surprising that a supranational model can be both more effective at serving the specific needs of small, highly specialized customer groups, but also at a dramatically reduced cost.

A top 15 biopharma company has quantified the economic impact after transforming a traditional affiliate model into a pan-European business unit focusing on a niche specialty care product (see Figure 4).

It led to a 32% increase in sales and a 10% higher market share. Efficiency measured by sales per FTE increased by an impressive 75%, also driven by a significant headcount reduction of 25%. The combined effects led to an operating profit increase of 52%, while lowering the operating expenses/ sales ratio by 34%. The compelling business case for a pan-European BU led to a portfolio and geographic extension two years after the foundation of the novel supranational unit.

A multi-talented team for a multi-country approach

Based on our rich experience with supranational Go-to-Market models we can support our clients quickly and pragmatically. We have further case studies, best practices, insights and benchmarks we can share with you.

In addition to facilitating fast decisions, we have also accelerated buildup and managed lean operations for our clients. Our teams are led by biopharma executives with hands-on managerial experience and consultants with significant project experience, including large scale transformational programs (see figure 5).

If the following situations sound familiar to you, please reach-out to us to discuss how supranational models may be relevant for you:

- A biopharma company is launching a small specialty care product targeting new stakeholders. The product is going to compete with very strong global competitors, already active in the field for a long time. Given planned growth trajectory and profitability targets, affiliates are not going to dedicate adequate resources to the product, and struggle particularly with high fixed costs for office-based roles.

- A biotech company has successfully developed their lead product for a rare disease indication and intends to commercialize the product instead of out-licensing to build own presence. The treatment will be used in tertiary centers and only a small number of patients will be newly diagnosed per country. Larger specialty care indications for the product will be ready two years after the initial launch at the earliest.

- A biopharma company is committed to launching a first specialty care product in a new therapy area across all its global markets to maximize patient access and enter the segment. Smaller countries, for example in Central and Eastern Europe or Latin America, struggle with insufficient critical mass to build affiliate business unit structures. Given prior focus on primary care, there is limited experience with regional/ cluster models.

References

(visit www.executiveinsight.ch/publications for download)

“Pan-European Specialty Pharma Businesses”, Executive Insight AG, July 2014

“How to commercialise narrow indication products”, Pharma Magazine, Nov/Dec 2012

“Organisational Polygamy”, Pharmaceutical Executive Europe, December 2008